Francisco Fernando

Francisco Fernando’s trickery

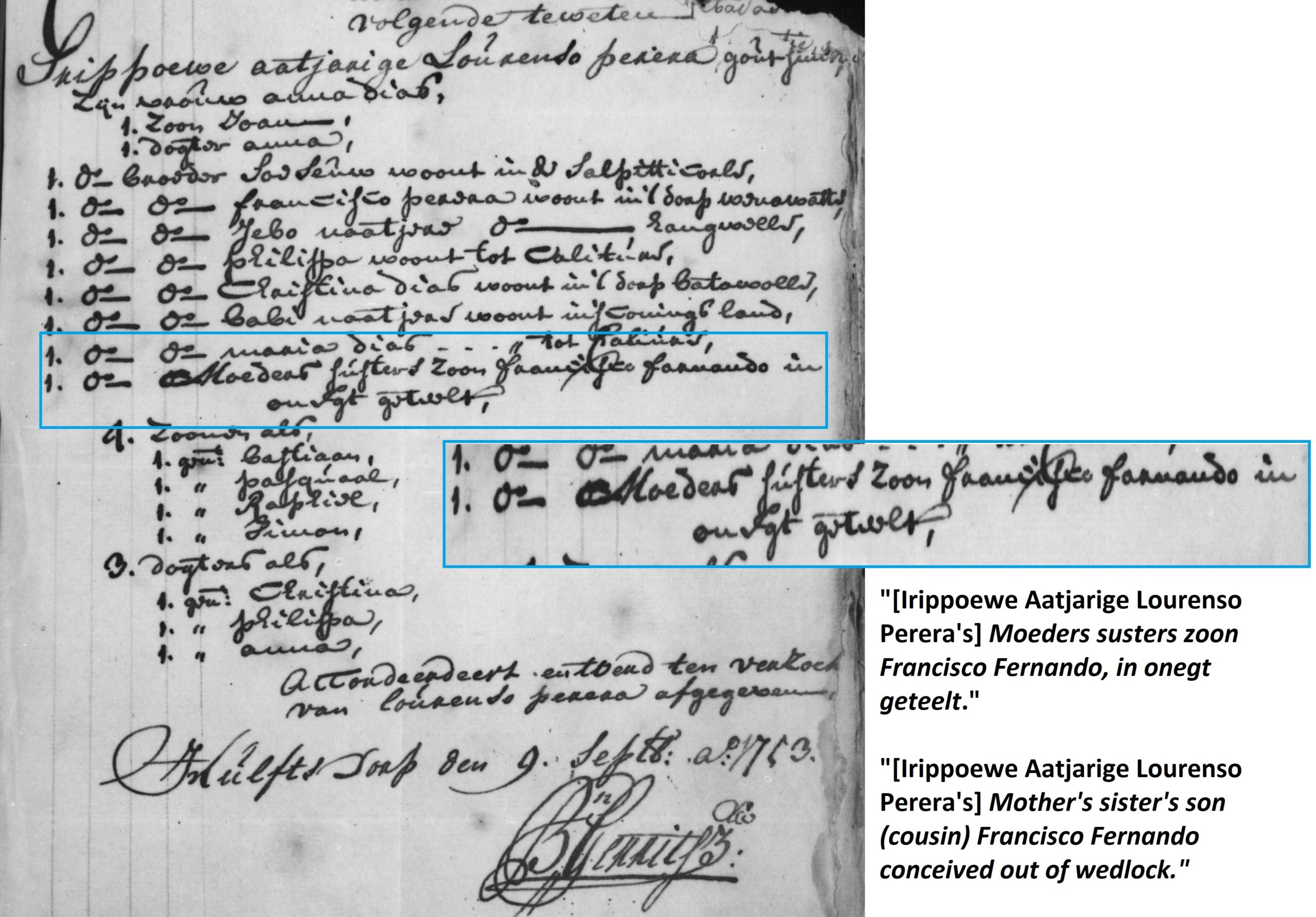

What urged Lankans to seek justice through VOC institutions? Conflict over property and inheritance is one of the themes that recurs most frequently in the historical records. Fransciso Fernando’s story illustrates just how that worked. It is a tale of treachery and trickery and how family conflict over land got embroiled into matters of registration, recognition and legitimacy.

Francisco's trickery

By Luc Bulten

It had taken Francisco Fernando many hours of walking through the muddy footpaths of the forested hills in Sri Lanka’s southwest to reach the boundary between the Dutch territories and those of the Kingdom of Kandy. The entire journey from his home village of Dedigamuwa to the border town of Avissawella had been an anxious ordeal. He was a wanted man, a fugitive. The warrant that had issued Francisco’s arrest had left him no choice but to pick up all of his belongings he could carry. Everything else he left behind, including the lands he had inherited from his late mother. Ironically, protecting this property had led him to the deed that had caused the local preacher to summon for his incarceration in the first place.

Franscico had, in front of the church-eldermen, pretended to be his half-brother in order to get his own marriage recognised. It looks like Francisco had been desperate. This act might have been his only option to legally inherit and secure his share of the family’s estate. The same family that had called Francisco’s mother a “concubine”, and Francisco himself a heathen and an illegitimate child.

Francisco’s story is a tale of treachery and trickery, and how a family conflict over their lands got embroiled into matters of registration, recognition and legitimacy.

Francisco’s youth in Dedigamuwa

How had Francisco ended up in this situation? His troubles had started many years ago in Dedigamuwa. Before he was born his mother’s family had taken in an orphaned girl and raised her as their own. This was common practice in the village at the time. Following local custom, a marriage was arranged where the two ‘sisters’ would marry one and the same man. In the years that followed the family expanded rapidly. The adopted sister, Louisa, gave birth to eight children. The other sister, Poentie, had but two children and Franscico was one of them. It was tradition among the āchāriCaste of artisans, primarily smiths and carpenters. Primarily known in the Dutch sources as black, silver and goldsmiths. More caste community, that sons followed their father’s footsteps. Francisco was destined to become a gold smith in Dedigamuwa. So both wives, their husband, and their respective children lived together in the village for some time. But misfortune struck Francisco’s side of the family, when his mother passed away.

His father’s deceit

Not long after the death of Francisco’s mother, in 1710, his father decided to formally marry Francisco’s aunt (his mother’s adoptive sister) before the Dutch Reformed ChurchWhen the Dutch came to Sri Lanka, they brought their church with them. This Protestant institution was known as the ‘Dutch Reformed Church’. It built churches in cities and villages all over the island, these also functioned as protestant schools, led by often local schoolmasters. In these schools children were taught reading and writing in their vernacular, on the basis of Reformed texts. More in Colombo. Why he did so, we do not know. But it was to have a long lasting impact on Francisco’s life. The Dutch protestants had very rigid ideas about marriage and family life. Children born out of relationships that were not endorsed by the church were considered illegitimate. Through the protestantWestern Christianity is divided into two main denominations, Catholicism and Protestantism. The latter was dominant in the Netherlands. In Sri Lanka it was specifically the Dutch Reformed Church, a protestant form of Christianity that functioned as the official church of the VOC. More marriage between Francisco’s father and his aunt the family became divided. While his half-brothers were subsequently all baptised and included into the Dutch Reformed community of the village, Francisco and his sister had to manage on their own. In August 1710 they were registered in the parish records as ‘illegitimate children’. And in hindsight, Francisco’s mother became cast as the ‘concubine’ of Francisco’s father by the community. Francisco and his sister were now seen as ‘heathens’ and outsiders. While Francisco’s father was investing in ‘the other half’ of his family, Francisco lived on his mother’s land, once granted to her as a wedding present by her parents. As life went on, he met and married a woman and started his own family. The couple had seven children.

A trickster at work

When Francisco and his wife were growing older, they attempted to improve their position within the community and secure a safe future for his family. So Franscico reached out to the resident preacher to have him and his wife officially married before the Dutch Reformed ChurchWhen the Dutch came to Sri Lanka, they brought their church with them. This Protestant institution was known as the ‘Dutch Reformed Church’. It built churches in cities and villages all over the island, these also functioned as protestant schools, led by often local schoolmasters. In these schools children were taught reading and writing in their vernacular, on the basis of Reformed texts. More as well. Being registered as an illegitimate child and as someone who had never been baptised, he must have realised that there was little chance for his marriage to be accepted by the church. It was for that reason that he tried to trick the aldermen and posed himself as his half-brother, lawful member of the Fernando family. The family of his half-brother was locally renowned for their skills as goldsmiths and known to be ProtestantWestern Christianity is divided into two main denominations, Catholicism and Protestantism. The latter was dominant in the Netherlands. In Sri Lanka it was specifically the Dutch Reformed Church, a protestant form of Christianity that functioned as the official church of the VOC. More. Therefore the preacher easily agreed to marry Francisco and his wife.

It did not take long before Franscico was unveiled as a con-man, by his own half-brother. Outraged by Franscico’s deceit the minister was quick to issue a warrant for Francisco’s arrest. Fearing not only the formal punishmentCorporal punishment was common in society at the time, and consisted of for example flagellation, branding and forced labour. More, Francisco probably also foresaw the communal backlash this would cause. And decided to pack up and flee to Kandy.

Crossing borders

Crossing the border with Kandy was a conscious act. In fact it was a well-known practice among Sinhalese who wanted to evade Dutch demands for taxation or service labour. Once they reached Avissawella they might have met other families or individuals who were looking to evade colonial law[refer to longread on mobility] More. We cannot be sure whether he travelled to Kandy alone, or with his family. Neither do we know how he made a living there, presumably as a landless peasant performing labour. He did not stay in Kandy for long though. Perhaps it was the feeling of injustice that had been done to him, or the fact that he was now again cast as an outsider by his own community, that eventually drew him back. But we do know that after several years in Kandy, he decided to head back Dedigamuwa to claim what was rightfully his.

And so it was in the year 1753, that Francisco and his eldest son returned to Dedigamuwa, only to find that his half-brothers had now occupied the lands that had he had inherited from his own mother. Moreover, Franscico’s half-brothers had managed to register these lands under their own names in the Dutch thomboFrom the Portuguese ‘tombo’, which translates as tome or volume, these land and population registers had pre-colonial roots in the palm-leaf inscribed ‘lēkam miti’ registers. First translated by the Portuguese, by the second half of the eighteenth century under Dutch these centralised registers contained the names of hundreds of thousands of local inhabitants and their property in the form of sowing fields, gardens and plantations. Read more in our longread. More. This time they had tricked the Dutch, and successfully so. Infuriated as he must have been, Francisco reached out to the one institution he thought might help him reclaim his mother’s lands: the LandraadLiterally translates as ‘land council’ or ‘rural council’, this colonial court dealt with legal conflicts between mostly local litigant parties. Additionally they were responsible for the maintenance of the population and land registers known as the thombos. More. Throughout the numerous sessions in Hulftsdorp that were held to weigh his claims, Francisco stood against his half-brothers in court. Fransisco’s old friends from the village vowed for him in court, and pleaded to the LandraadLiterally translates as ‘land council’ or ‘rural council’, this colonial court dealt with legal conflicts between mostly local litigant parties. Additionally they were responsible for the maintenance of the population and land registers known as the thombos. More to return the lands to him and correct what was documented in the thomboFrom the Portuguese ‘tombo’, which translates as tome or volume, these land and population registers had pre-colonial roots in the palm-leaf inscribed ‘lēkam miti’ registers. First translated by the Portuguese, by the second half of the eighteenth century under Dutch these centralised registers contained the names of hundreds of thousands of local inhabitants and their property in the form of sowing fields, gardens and plantations. Read more in our longread. More.

Caught by the Kandyan war

The claims and statements went back and forth and the court case dragged on for years. When after seven years, the council members of the LandraadLiterally translates as ‘land council’ or ‘rural council’, this colonial court dealt with legal conflicts between mostly local litigant parties. Additionally they were responsible for the maintenance of the population and land registers known as the thombos. More were about to pronounce their verdict, war broke out. During the Kandyan-Dutch war, the judicial apparatus of the Company grinded to a halt. In 1767, peace finally returned to the regions bordering Kandy and the Dutch colonial territories. And so it took another seven years, before the LandraadLiterally translates as ‘land council’ or ‘rural council’, this colonial court dealt with legal conflicts between mostly local litigant parties. Additionally they were responsible for the maintenance of the population and land registers known as the thombos. More resumed its duties. By this time Franscisco, now old and frail, was still without his lands. As soon as he heard that the LandraadLiterally translates as ‘land council’ or ‘rural council’, this colonial court dealt with legal conflicts between mostly local litigant parties. Additionally they were responsible for the maintenance of the population and land registers known as the thombos. More was taking cases again, he travelled to Hulftsdorp. Perhaps he waited for his turn outside the disāva’s veranda like the people on the Brandes picture. Eventually in April that year his case was opened again.

A story without an end

But once the LandraadLiterally translates as ‘land council’ or ‘rural council’, this colonial court dealt with legal conflicts between mostly local litigant parties. Additionally they were responsible for the maintenance of the population and land registers known as the thombos. More finally decided to resume the long delayed case, Francisco had just died. Like many other endings, however, Francisco’s death brought on new beginnings as well: after fifteen years of litigation, it was now his son’s turn to reclaim their land and social status in Dedigamuwa. How that ended, the records do not tell us. But we do know that family disputes like this could drag on for centuries.