Gimara

Gimara's loss

Endless volumes of legal civil cases in the Sri Lankan National archives bear witness to the use of justice by eighteenth century Lankans. Family feuds over property were at the heart of most cases and could drag on for years. Land came with status, privilege and service, as well as food security. It was worth fighting for. But no matter how skilled Lankans were in navigating Dutch legal institutions, there was always the risk of being caught by surprise. Gimara’s story reminds us how capricious Dutch colonialism was and how this crushed Lankans in unexpected ways

Gimara's battle

Gimara’s life was turned upside down when her husband Daniel passed away. He had been a foot soldier or lascarinA lascarin was an indigenous foot soldier or guard. They performed a diverse set of services such as carrying messages, guarding gates or individuals, and policing. They were rewarded lands in compensation for their services. More, and her sons had taken over his service after his death, as well as the land attached to the position. The lands they owned produced enough food to feed Gimara’s family. But after Daniel’s death, her late husband’s siblings, Johan and Jantje, created trouble. They teamed up to push Gimara off her land, claiming Daniel had been an illegitimate child. They said that Daniel should not have taken up the service of foot soldier. Johan and Jantje laid claim to both the service and the accompanying land. Daniel’s siblings had brought the case to court, which had decided in their favour. However, Gimara did not let her in-laws get away with this, and appealed the case to the highest court in the district of Galle. And so Gimara and her two sons, Dinees and Mathees, travelled to the town of Galle in April 1790 to plead their case.

Gimara asked Johannes and Jantje in her plea why they were disputing her husband’s inheritance now, after he had passed away. She pointed out that his father had had Daniel registered in the thomboFrom the Portuguese ‘tombo’, which translates as tome or volume, these land and population registers had pre-colonial roots in the palm-leaf inscribed ‘lēkam miti’ registers. First translated by the Portuguese, by the second half of the eighteenth century under Dutch these centralised registers contained the names of hundreds of thousands of local inhabitants and their property in the form of sowing fields, gardens and plantations. Read more in our longread. More as his legitimate child back when he was eight years old. With such a line of questioning Gimara aimed at unveiling the inconsistencies in the claim of her in-laws. But the real question she indirectly raised was: In whose eyes was her husband deemed illegitimate? Gimara stood up, not only against her in-laws, but also against the Dutch judges who presided over the court.

Family ties

Daniel’s father Philippu had been a lascarinA lascarin was an indigenous foot soldier or guard. They performed a diverse set of services such as carrying messages, guarding gates or individuals, and policing. They were rewarded lands in compensation for their services. More, and along with that service came duties such as carrying messages, serving summons and keeping guard for high officials. Being a lascarinA lascarin was an indigenous foot soldier or guard. They performed a diverse set of services such as carrying messages, guarding gates or individuals, and policing. They were rewarded lands in compensation for their services. More would have added to Philippu’s social status in the village and it came with the attraction of inheritable rights over arable land. Daniel was Philippu’s only son and he was born out of Philippu’s union with Jibika. Philippu must have been relieved to have Daniel as his heir, as this secured the family’s well-being. After all he had plenty of mouths to feed, as his marriage with Jibika’s sister Juliana had brought him three daughters. The multiple gardens and paddyfields yielded them the necessary basics. When in 1751 the thombo writerThombo writer (or: thombo keeper): The commissioner responsible for the upkeep of the head, and land thombos. It seems an additional thombo keeper was appointed for the upkeep of the school thombos, the school/church registers. More registered the lands, Philippu made sure that all his properties were described as such and that Daniel was entered as his rightful son.

After Philipu’s death Daniel followed in his father’s footsteps. Daniel married Gimara and must have felt blessed with their two sons, Dinees and Mathees, securing the lascarinA lascarin was an indigenous foot soldier or guard. They performed a diverse set of services such as carrying messages, guarding gates or individuals, and policing. They were rewarded lands in compensation for their services. More service and the livelihood of the next generations. Juliana’s three daughters meanwhile also got married, and moved out of the village. Eventually, two of their husbands, Johan and Jantje, returned to trouble Gimara.

Philippu’s deceit?

When Philippu had Daniel entered as his offspring with Juliana, either he had deliberately lied when the thombo writerThombo writer (or: thombo keeper): The commissioner responsible for the upkeep of the head, and land thombos. It seems an additional thombo keeper was appointed for the upkeep of the school thombos, the school/church registers. More registered the village in 1751, or the thombo writerThombo writer (or: thombo keeper): The commissioner responsible for the upkeep of the head, and land thombos. It seems an additional thombo keeper was appointed for the upkeep of the school thombos, the school/church registers. More accepted Philippu’s union with Jibika and did not object to recognising Daniel as his offspring.

The situation would eventually haunt Gimara. Philippu had entered Daniel as his legal son in the thomboFrom the Portuguese ‘tombo’, which translates as tome or volume, these land and population registers had pre-colonial roots in the palm-leaf inscribed ‘lēkam miti’ registers. First translated by the Portuguese, by the second half of the eighteenth century under Dutch these centralised registers contained the names of hundreds of thousands of local inhabitants and their property in the form of sowing fields, gardens and plantations. Read more in our longread. More to safeguard the family lands, while his union with Jibika was by Dutch standards out of wedlock. After Daniel’s death Johan and Jantje decided to take Gimara and her two sons to court because they disputed the legitimacy of their claims to Daniel’s lascarinA lascarin was an indigenous foot soldier or guard. They performed a diverse set of services such as carrying messages, guarding gates or individuals, and policing. They were rewarded lands in compensation for their services. More service. In fact, in their view, Daniel had not been the rightful heir in the first place. When the case was heard first in 1788, two Dutch and two local members of the LandraadLiterally translates as ‘land council’ or ‘rural council’, this colonial court dealt with legal conflicts between mostly local litigant parties. Additionally they were responsible for the maintenance of the population and land registers known as the thombos. More were present. They ordered an investigation in the village. The keeper of the thomboFrom the Portuguese ‘tombo’, which translates as tome or volume, these land and population registers had pre-colonial roots in the palm-leaf inscribed ‘lēkam miti’ registers. First translated by the Portuguese, by the second half of the eighteenth century under Dutch these centralised registers contained the names of hundreds of thousands of local inhabitants and their property in the form of sowing fields, gardens and plantations. Read more in our longread. More, members of the LandraadLiterally translates as ‘land council’ or ‘rural council’, this colonial court dealt with legal conflicts between mostly local litigant parties. Additionally they were responsible for the maintenance of the population and land registers known as the thombos. More, the village headmen and all the heirs were required to be present.

It is not difficult to imagine the spectacle in the village, when the investigation took place. Fellow villagers would have been intimately acquainted with the details of the case. At the inquiry, Jibika confirmed Daniel’s nonmarital birth. Daniel’s brothers-in-law Johan and Jantje played their trump card: documentary proof that Daniel had been baptised under his mother’s name! Jibika, they claimed, had not known till after Philippu’s and Juliana’s death that her son had been entered in the thomboFrom the Portuguese ‘tombo’, which translates as tome or volume, these land and population registers had pre-colonial roots in the palm-leaf inscribed ‘lēkam miti’ registers. First translated by the Portuguese, by the second half of the eighteenth century under Dutch these centralised registers contained the names of hundreds of thousands of local inhabitants and their property in the form of sowing fields, gardens and plantations. Read more in our longread. More as their son. Philippu had secured the family’s patrimony, but his sons-in-law Johan and Jantje now turned against Daniel’s offspring. By framing Daniel as ‘illegitimate’ they presented themselves as the rightful heirs to both the lascarinA lascarin was an indigenous foot soldier or guard. They performed a diverse set of services such as carrying messages, guarding gates or individuals, and policing. They were rewarded lands in compensation for their services. More service and the lands.

Trumping the in-laws

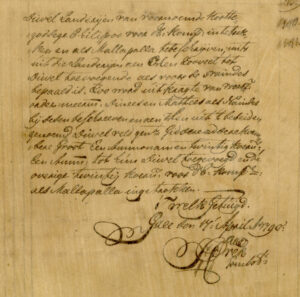

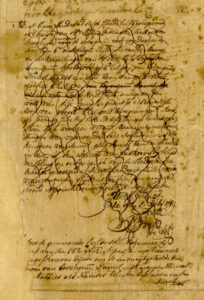

Gimara was cornered by her in-laws, but she would not give up. She produced a lascarinA lascarin was an indigenous foot soldier or guard. They performed a diverse set of services such as carrying messages, guarding gates or individuals, and policing. They were rewarded lands in compensation for their services. More deed of Philippu’s from 1769. But her own trump card took the form of a Sinhalese report from the LandraadLiterally translates as ‘land council’ or ‘rural council’, this colonial court dealt with legal conflicts between mostly local litigant parties. Additionally they were responsible for the maintenance of the population and land registers known as the thombos. More councillor Don Balthasar Abeysinghe himself. Don Balthasar was an influential man in the region, being son of the ‘gate mudaliyārOne of the highest ranking indigenous chiefs in colonial times. Traditionally a military title, under colonial rule it became an important administrative office as well. More’ Nicolaas Dias Abeysinghe. Had she known the man prior to the court-case? Was she connected to his family? We can only guess.

However, as it turns out, having this one powerful man vouch for her in the LandraadLiterally translates as ‘land council’ or ‘rural council’, this colonial court dealt with legal conflicts between mostly local litigant parties. Additionally they were responsible for the maintenance of the population and land registers known as the thombos. More, was not sufficient. All the LandraadLiterally translates as ‘land council’ or ‘rural council’, this colonial court dealt with legal conflicts between mostly local litigant parties. Additionally they were responsible for the maintenance of the population and land registers known as the thombos. More members agreed that Daniel was an ‘illegitimate’ child. Luckily for Gimara the members disagreed on the consequences, and eventually it was decided by majority vote that the two parties were to share the service and lands.

On 1 July 1789 the thombo-keeper was instructed to insert a note in the registers that Daniel was ‘illegitimate’, which we can still read to this day. On the service and lands, the entry further specified they would be enjoyed in turns by male descendants of Philippu’s ‘legitimate’ daughters and Daniel’s children.

The eye of the beholder

Still, Gimara was unable to let go, and she appealed to the High Court in Galle. Here only European men presided, but Gimara was not intimidated. The ties among Philippu, Jibika and Juliana were common from her point of view, and therefore she openly questioned the idea of illegitimacyIn Sri Lanka illegitimacy was only known in regard to children born from people from different castes. In the colonial period illegitimacy became very important, since European norms caused those born out of (a Christian) marriage to be considered illegitimate and this made them lose privileges such as inheritance rights. More in court. IllegitimacyIn Sri Lanka illegitimacy was only known in regard to children born from people from different castes. In the colonial period illegitimacy became very important, since European norms caused those born out of (a Christian) marriage to be considered illegitimate and this made them lose privileges such as inheritance rights. More was an irrelevant concept, if a father publicly designated his son as his heir. This is what Philippu had done when entering Daniel into the thomboFrom the Portuguese ‘tombo’, which translates as tome or volume, these land and population registers had pre-colonial roots in the palm-leaf inscribed ‘lēkam miti’ registers. First translated by the Portuguese, by the second half of the eighteenth century under Dutch these centralised registers contained the names of hundreds of thousands of local inhabitants and their property in the form of sowing fields, gardens and plantations. Read more in our longread. More.

But little did Gimara know, that through her honest appeal, she would set in motion a process that spun out of her control. Rather than just labelling him as illegitimate, the appellate court concluded that Daniel was ‘born of incest’, and noted that Jibika and the village headman had confirmed this without restraint. Partnering with a spouse’s sibling was banned as incestuous by Roman-Dutch law, in a bid to prevent polygamy. But that was not all, as the judges also decided that in hindsight, Daniel should never have been a lascarinA lascarin was an indigenous foot soldier or guard. They performed a diverse set of services such as carrying messages, guarding gates or individuals, and policing. They were rewarded lands in compensation for their services. More “due to his illegitimate birth”. Philippu, they said, was not survived by any male heirs; so they withdrew the service from the family altogether.

As a result, the original thomboFrom the Portuguese ‘tombo’, which translates as tome or volume, these land and population registers had pre-colonial roots in the palm-leaf inscribed ‘lēkam miti’ registers. First translated by the Portuguese, by the second half of the eighteenth century under Dutch these centralised registers contained the names of hundreds of thousands of local inhabitants and their property in the form of sowing fields, gardens and plantations. Read more in our longread. More note was struck off and followed by a new note dated 17 April 1790: the service paddy-field was now appropriated by the company. [pic new entry]. The Company as the most powerful player in the field had trumped both litigating parties.