Landraad

The landraad

The Landraad was a court of first instance at the bottom of the legal hierarchy in eighteenth-century Sri Lanka. A mixed body of councillors, both European and local, served on it. However, they had varying degrees of power. The local councillors for instance were not allowed to vote. The European, ‘white’ members were considered more important for the operations of the Landraad than the local members. This essay will introduce the procedure followed in the Landraad, its personnel, the society that came before it and the types of cases that it handled. It will explore whose law was used in the forum, and how decisions were arrived at. The Landraad will be located in the specific time and locations that it operated in, providing an analysis for its successes and failures.

The Landraad: local disputes and land registration

In 1780, Kalegana Bastian Naidelage Maria of Dutch-controlled Galle in southern Sri Lanka was served with summons to appear before a certain judicial forum. She was reported to have brazenly responded that even her dog would not appear before that judicial forum, the Landraad, that had summoned her. The Landraad decided that Maria would be flogged for her insult. Maria’s brashness reveals how locals subverted the authority of their early colonial rulers.

Still, the Landraad (or Land Council) of eighteenth-century Sri Lanka, played a significant role in the governance and administration of the island during that period. As an institution, it served as a key authority in matters related to land ownership, land disputes, and the management of land-related issues. This essay explores the origins, composition, functions, and significance of the Landraad, shedding light on its historical importance in eighteenth-century Sri Lanka.

The origins of the Landraad can be traced back to seventeen-century Dutch colonial rule in Sri Lanka. The Dutch East India Company gained control of the coastal areas of the island and established a system of administration that included various legal institutions to govern different aspects of the colony. The Landraad emerged as a key institution to deal with land-related matters and ensure proper management of the land under Dutch control.

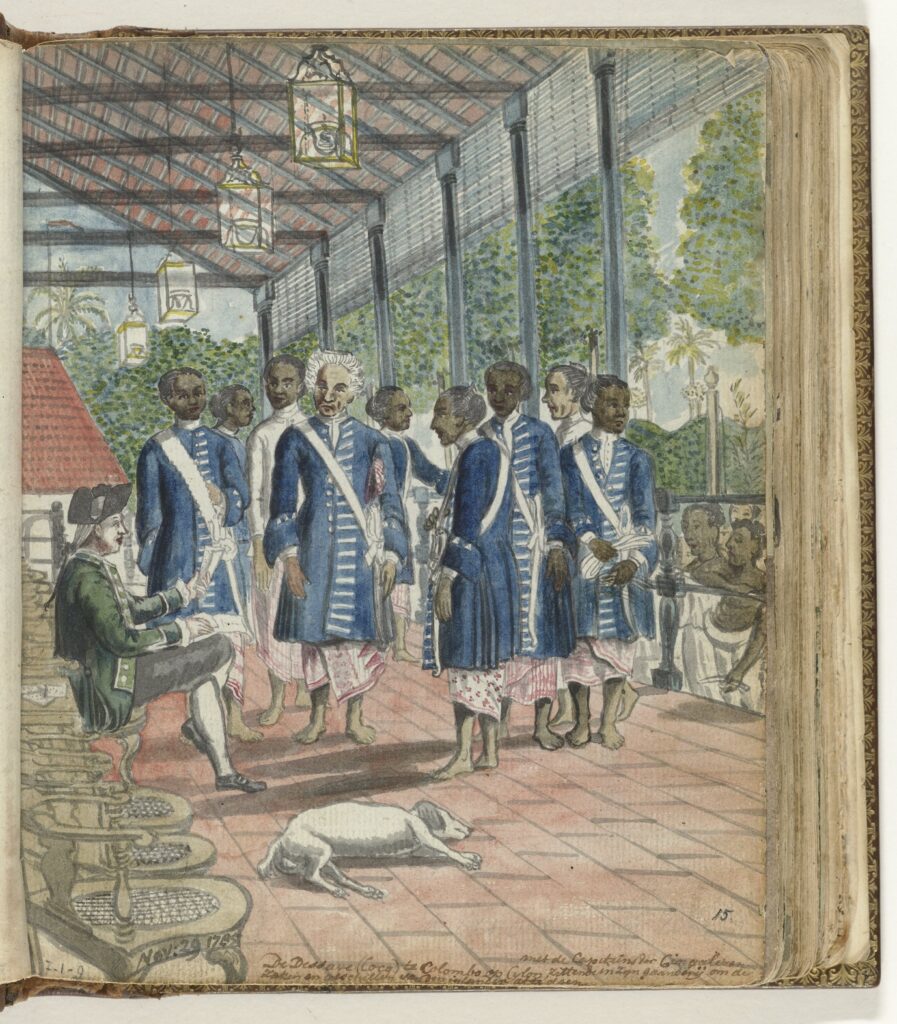

The Landraad was composed of councillors who were appointed because they were employees of the Dutch East India Company, along with a number of councillors who were selected from the local population. The president of the Landraad was also the overseer of the Galle district, who was usually a high-ranking European official. Effective control of the Landraad was held by the European councillors.

The local councillors were often influential local elites, native chiefs, or mudaliyars, who were familiar with the customs, traditions, and land tenure systems of the island. But, they did not have the power to vote in the council. It may be imagined that the inclusion of local councillors ensured the participation of the native population. Yet, many meetings of the Galle Landraad, for instance, were not attended by the local councillors. If insufficient numbers of European members were present, action was taken to ensure that more members would be present at following meetings. The European councillors, at the least, would participate in discussions with the Governor in Council in Colombo to standardise practices of registering land tenure and other related matters.

A wide variety of social formations, including both men and women, came before the Landraad. In general, the Landraad served as a court of first instance, positioned in the judicial hierarchy above village chiefs who held initial authority. Individuals were allowed to reject their decisions and approach the Landraad in certain circumstances, as you can read in the live stories of Gimara and Kobywattege Annika. It is plausible that headmen primarily settled minor crimes and disputes, but in cases involving significant property matters, indigenous litigants could turn to the Landraad if they were dissatisfied with the ruling of lower-ranking headmen, overseers, or commanders. Additionally, if European officials deemed a case beyond their capabilities, it could be referred to the Landraad for adjudication.

The functions of the Landraad were multi-fold. Its primary role was to adjudicate land disputes and settle conflicts arising from land ownership, boundaries, and inheritance. The councillors would hear the cases brought before them, examine relevant documents and testimonies, and render judgments based on the existing laws, regulations and consensual decision-making. A combination of both Roman-Dutch law and local laws was used. The Landraad’s decisions were considered binding and potentially played a crucial role in maintaining social order and resolving conflicts within the colonial society.

Another significant function of the Landraad was to oversee the management of land resources. The council played a vital role in recording ownership of land in special registers, the thombos, ensuring proper land utilisation, and collecting revenue from land-related activities. It also regulated land transactions, leases, and transfers, aiming to retain the cinnamon growing on such land by imposing conditions against the destruction of that spice.

The Landraad’s significance in eighteenth-century coastal Sri Lanka cannot be overstated. It provided a forum for the resolution of land disputes and conflicts. Its role in managing land resources helped establish recognition of the existing system of land tenure that promoted agricultural productivity. By enforcing land laws and regulations, and ensuring the registration of the thombo, the Landraad contributed to the maintenance of order and justice in the Dutch-controlled territories.

Moreover, the Landraad served as an important link between the early colonial administration and the local population. The inclusion of native councillors not only facilitated the understanding of local customs and traditions but also enabled, at least to some extent, representation and participation of the local elites in the decision-making process.

It is important to note that the Landraad, like any other colonial institution, was not without its flaws and limitations. Its decisions were influenced by the colonial interests of the Dutch authorities, and the local population often faced challenges in asserting their rights and grievances.

In this way, the Landraad of eighteenth-century Sri Lanka played a crucial role in the governance and administration of land-related matters during Dutch colonial rule. It also impinged on family law. As an important legal institution, it facilitated the resolution of land disputes, managed land resources, and enforced laws and regulations in relation to the ownership of land.