Dutch Reformed Church

The ambiguities of the Dutch Reformed Church

In many of the life stories on this website, the Dutch Reformed Church played an important role. By the end of the 18th century 300.000 persons were registered as being baptised, nearly one third of the population in the maritime provinces. This seems to be at odds with the usual image of Sri Lanka with its strong and influential Therevada Buddhism, besides popular Hindu, Islamic and Catholic traditions. At present the Protestants are the smallest religious group on the island. So what was at stake here? What role did the Protestant church play in society, what kind of institution was it? Why were so many people baptised and why did they seek contact with te church?

The arrival of Protestantism

When the Dutch came to Sri Lanka in the 1630s, they brought their religion with them, a Christian, Protestant institution known as the ‘Dutch Reformed Church’. The reformed church was a particular branch of the Protestant church. Protestant Christianity had been newly formed in the early sixteenth century during the Reformation, opposing the Roman Catholic church headed by the pope in Rome. The young Dutch republic was formally Protestant and wanted to further expand what they considered their one true religion. The Republic was also a growing colonial empire, with trade networks in the Indian Ocean. Their economic and religious objectives went hand in hand. In the Indian Ocean they encountered, among others, their main European rival of this period. The Portuguese were outspokenly Catholic and had send many missionaries along their colonial enterprises across the Indian Ocean, such as in India, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. Starting from the 1630s the Dutch conquered the coastal areas of Sri Lanka on the Portuguese. A large Catholic community remained after the Portuguese had left, and the Dutch considered them not only a threat to their religion but also their political power. The religious wars between Protestants and Catholics in Europe were also an important factor in the rivalry between Dutch Protestants and Portuguese Catholics.

The church concentrated around Colombo, Galle, and Jaffna, where the Dutch had declared their official jurisdiction. In 1647 the Dutch Reformed Church building in Galle, that still stands, was in use for the first time. The protestant Church services were in either Tamil, Sinhala, Dutch or sometimes Portuguese. Because aside from the churches built in the Dutch forts all over the island, there were churches built in the villages outside the cities, especially on the southwest coast and around Jaffna. Often the churches were built on the sites of former Catholic churches, either repurposing the building or destroying the old building. The Catholic churches in their turn had often been built on or near existing Hindu and Buddhist temples or sacred places: places of religion were disrupted and reshaped throughout the Portuguese and Dutch period. Over the course of the eighteenth century, especially after the Kandyan wars and the decline of Portuguese power in Asia, the Dutch Protestants cooperated more with the Catholics, tolerating their existence as well as the traveling Oratorian missionaries from Goa.

Schools and colonial governance

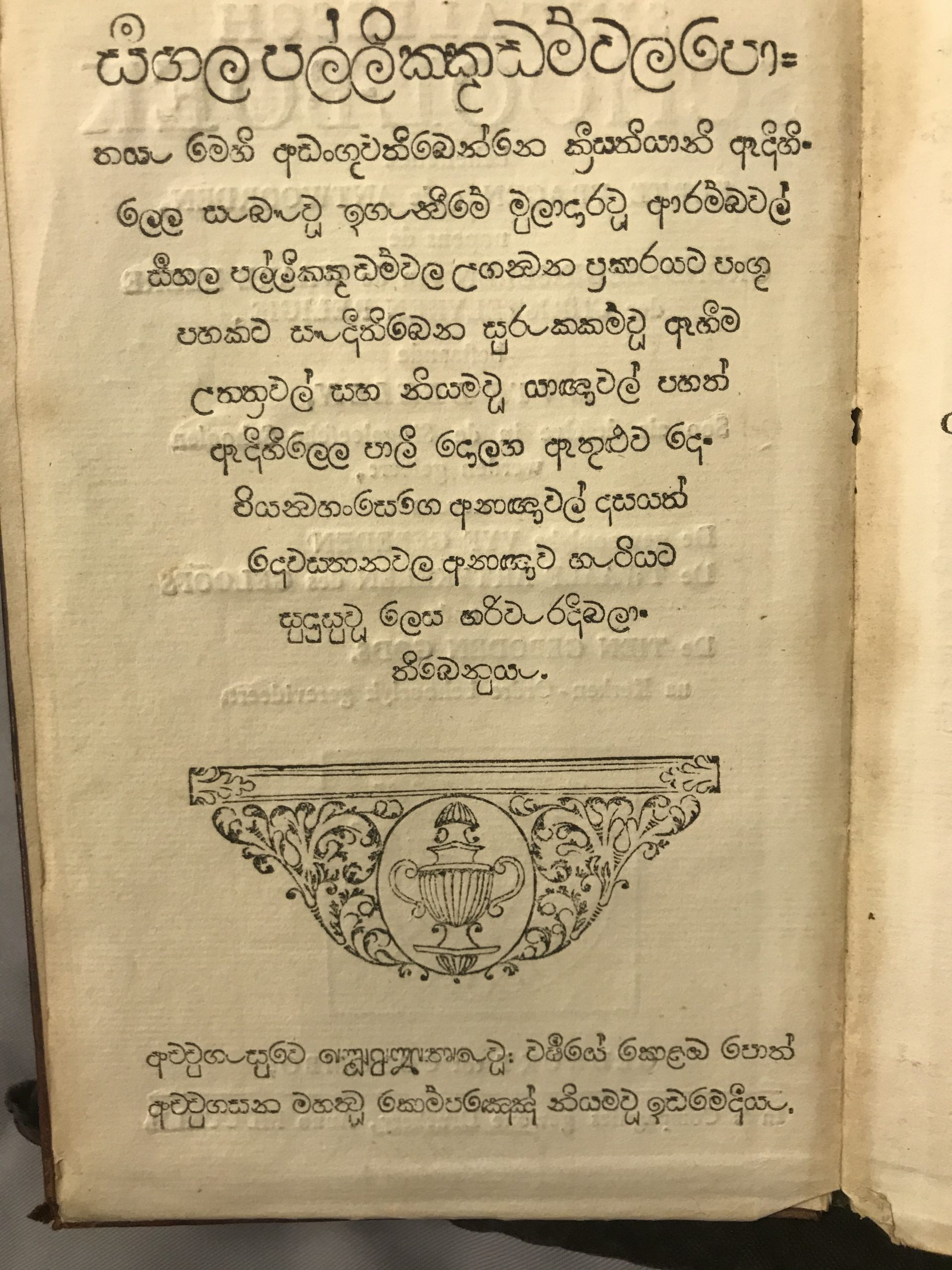

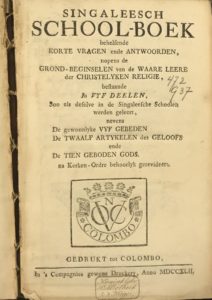

The protestant churches in the villages also functioned as protestant schools, led by often local schoolmasters. This function seems to resemble the function of the Portuguese church as well as the Buddhist temple before that. Religion and education were intertwined. In the Dutch Reformed schools, children were taught reading and writing in their own language, on the basis of translated Dutch Reformed texts such as the Heidelberg Cathechism and prayer books.

The schools were located in central, villages of considerable size, such as Kalutara or Wattala. Per school, several smaller villages or communities ‘belonged’ to this school: in Wattala, as we see in the life story of Francina Farnando, this meant that children from several different caste groups and geographic locations were registered to one school. In some schools, there were three hundred children in attendance between the age of six and seventeen. In other schools, children seldom came to school, much to the dismay of the church leaders. They fined the children or reprimanded the schoolmaster in this case.

The schools in the city and country side were to be regularly visited by a Dutch Reformed minister, who, unlike the schoolmaster, was allowed to perform baptisms, deem students ready to leave school and consecrate marriages. The visitation took place on roughly the same date each year, with a procession of minister, clerks, government officials, lascarin soldiers and enslaved servants traveling several schools on one ‘tour’ of several months. All gathered in the school building, the minister would pray, give a sermon and continue the examinations as well as the ritual ceremonies of baptism and marriages. He also reprimanded those of the community who were said to be ignoring the the rules of the school and church: who had children out of wedlock or had not baptised their children.

Instrument of colonialism

The village church and school functioned as extension of the colonial state. The church was also the place where the printed government ordinances, in Sinhala and Tamil and Dutch were read out loud and pasted on the wall. The entangled connection between church and state, or Company in this case, is even more clear in the administrative role the Church had in Sri Lanka, for example in keeping parish records (school thombos). By the end of the eighteenth century, almost 300.000 people were registered as baptised in the Protestant church.

It was the village schoolmaster, who kept and reported birth dates, marriage dates, and baptism numbers. He functioned both as a schoolmaster and village scribe. The schoolmaster was usually a member of one of the local families. Yet his position in the village was ambiguous to say the least: he represented the Dutch government and church, which empowered him, but at the same time he was often despised by the villagers because of it. There are several schoolmasters who complain about how they were beaten up, or who got involved in conflicts with the local community otherwise.

The Dutch wanted each school to have a well-educated schoolmaster, and therefore started Seminaries – advanced schools – near Jaffna and in Colombo. They were mainly aimed at sons of the Lankan elites, to train them in Dutch government, religion and culture. Some graduates of the seminaries could also go on to become ordained Protestant ministers by studying in the Netherlands, which was the scheduled future for Willem de Melho. Others became clerks in service of the VOC. Due to a shortage of seminarists, often schoolmasters were appointed from among particular local families who had in the past also delivered the village scribes. Thus at this level too we observe how colonial institutions were embedded in local practices.

Marriage and illegitimacy

For Lankans being baptised by the church could be an asset, because it gave access to the Dutch education system, services and the legal system. This is why the Church played such a big role in disputes over property rights, which stand at the basis of the stories of Gimara, Francisco and others. To be officially married in the Dutch Reformed church, it was also required to be baptised. Marriage was relevant because it afforded, among others, legitimacy to children born in the marriage. In Sri Lanka illegitimacy had only been known in regard to children born out of inter-caste relations. In the colonial period illegitimacy became very important, since European norms caused those born out of (a Christian) marriage to be considered illegitimate and this made them lose privileges such as inheritance rights.

The official Dutch marriage was highly bureaucratized and consisted of many steps, such as: producing one’s baptism certificate or ola in order to get permission to marry from the “Committee for marital affairs” and once permission was received they were obliged to ‘put up the banns’ in public to get community approval and having this registered by the schoolmaster; after all steps were taken, the couple had to wait for a protestant minister to visit their village church and have him consecrate the marriage. Then, and only then, in Dutch view, the marriage was formal, official and registered into the marriage rolls. Although local marriage traditions and norms clashed with that of the Dutch, the community approval of a marriage compared to ‘putting up the banns’ in the Dutch system. As a result, many Sri Lankans who tried their hand at a Dutch legal marriage, simply skipped the final step – having it consecrated by the minister – on purpose or by accident. Though to Sri Lankans such marriages were formal and intentional, they were considered immoral by the Dutch.

All these regulations resulted in Sri Lankans considering Protestant baptism and marriage a type of civil ceremony, rather than simply religious rituals. The ceremonies were an administrative hurdle to take, in order to navigate the Dutch administration. Many people only appear in the records when they were baptised or married. Barely any specific deaths of Sri Lankans are registered in the church records, despite the Dutch’s emphasis on the importance of this registration. Interaction with the church was often limited to baptism and marriage, since it served a practical purpose for Sri Lankans. The registration of death did not. The absence of this registration illustrates the ambiguous relation of Sri Lankans with the church.

Organisation of the Church

The church was organised by a Church Board (or Church Council, kerkenraad), which consisted of church elders and ministers. Jaffna and Galle had their own church board, but the Colombo board was the main board. A member of the Dutch colonial government was also part of the board: the Church was not allowed to make any decisions without permission of the VOC. Clerically the Colombo Church Board fell under the clerical jurisdiction of the Reformed Church in Amsterdam. Congregants were allowed to report to the church board either to ask permission for baptism, ask advice in marriage problems, or to be admonished about their non-Christian behaviour. This included Singalese and Tamil people, who requested special permission for baptism at a later age or wanted to get admission to the Holy Supper (the Protestant version of the Eucharist, a ritual with bread and wine remembering and symbolising the death of Jesus). The schools were governed by a School Board, or Scholarchale Vergadering. This board, similar to the Church Board, also commented and ruled over moral issues such as marriage, marriage registration and family feuds.

The Dutch Reformed Church, or DRC, still exists today in Sri Lanka, though it is called the Christian Reformed Church of Sri Lanka now. Catholicism however, is much more present in current day Sri Lanka. When the Dutch rule over Ceylon ended in 1796, the Church lived on, but mainly as a ‘Burgher’ church, a minority in Sri Lanka that traces its ancestry to Europeans that had moved to the island during Portuguese, Dutch and British colonial rule. Since mid-twentieth century however, the Church has been focused more and more on being part of Sinhalese and Tamil communities as well. Though the church has more often been studied as a part of the Eurasian Burgher community, given the demographic of the Church now it is interesting to study the origins of the Church and its interaction with these non-English-speaking communities in Dutch colonial Sri Lanka.